The knowledge of long-standing employees

A blog by Dr. Uwe-Klaus Jarosch, November 2025

In the blog “Knowledge – Management,”

I attempted to describe a few basics about what constitutes knowledge in companies and how it is “stored.”

In doing so, I limited myself to the “formal rules” within the company.

However, we humans have more than just formal rules in our heads that we use to work together as a company and apply knowledge.

When employees leave, a great deal of knowledge usually leaves the company with them. This is despite the fact that employees are praised and touted as the company’s most valuable asset.

But this knowledge is usually not an “asset” that can be valued in monetary terms. As a result, it seems more economical to dismiss people along with their knowledge from the company and even pay them severance pay.

Knowledge can’t be worth that much, can it?

I will examine how much knowledge should be worth in monetary terms in another blog post.

Here, I will focus on the question of how knowledge can remain in the company before employees leave.

Case 1: The expert who has always shared their knowledge with others.

Case 2: The specialist (including female specialists) who does their job intuitively and correctly thanks to their long experience, but who has so far only been able to pass on this knowledge through their role model function.

Case 1 is the simpler case for our consideration. Someone who shares his knowledge with others will usually have records that are also designed in such a way that third parties can understand and comprehend them.

In addition, such a person has learned and practiced explaining the knowledge to others, i.e., making it understandable and applying it to use cases.

If we look at this type of knowledge transfer, it consists of two steps:

a) documenting related knowledge modules and

b) explaining constraints. In most cases, it is only by explaining the constraints that other people will be enabled to apply the knowledge modules. Very few people have the genius to recognize these constraints themselves. And it is precisely these constraints, this explanation, that make the knowledge valuable in the first place.

In another context, I have described “explaining how it works” as “instructions for action.”

We now have a variety of ways to pass on such constraints: We can write step-by-step instructions. We can explain the constraints in a lecture. We can prepare this in writing, as audio, or even as video in order to pass on this content in condensed form and convey it in a short time. We can now also feed such explanations into AI systems, which then reassemble and present the network of prerequisites, knowledge building blocks, and derived application rules for the use case. This should not be mixed with publicly available large language models, which do not necessarily access knowledge, but feed freely from the world of publications and, unfortunately, increasingly from AI-generated content.

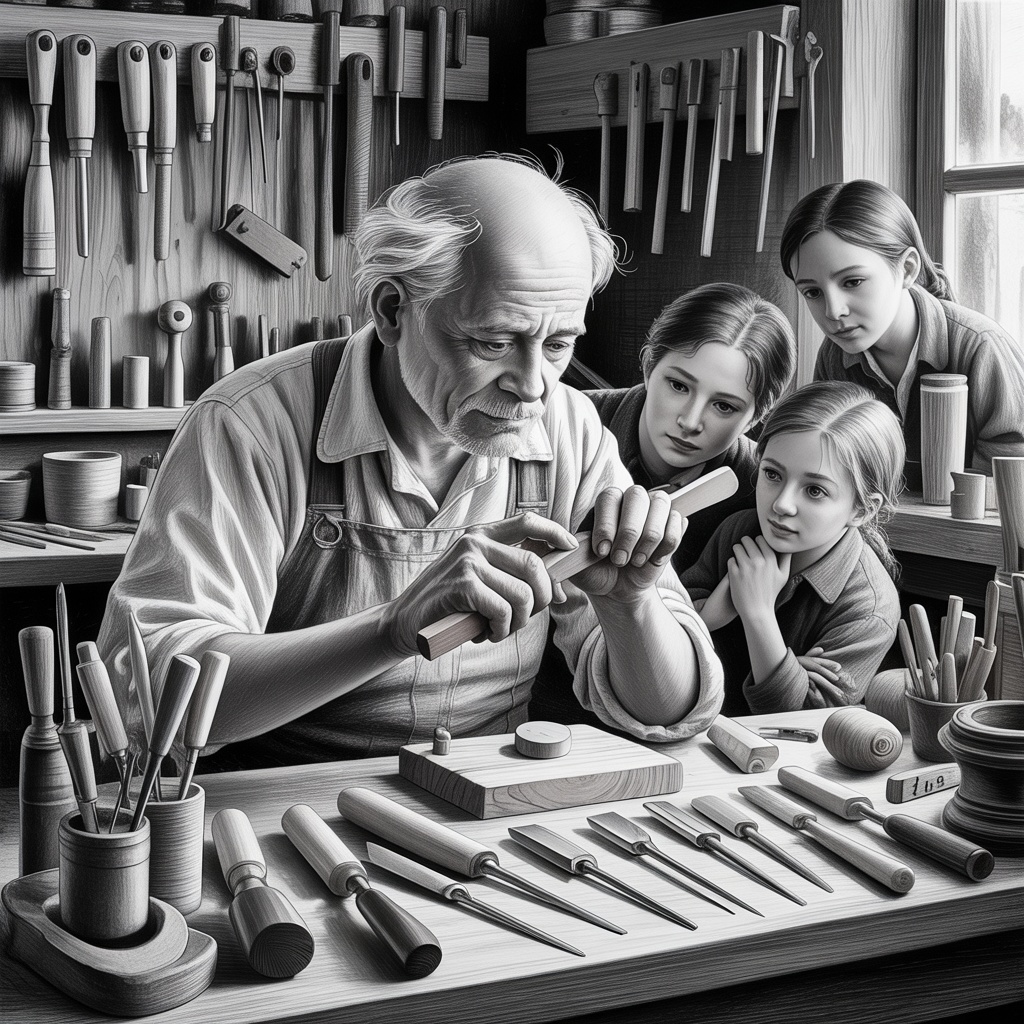

Case 2 is more complicated.

Master Eder has mastered his process in his sleep. He can respond correctly to every noise and every reaction in his environment. He has developed a feel for it.

Such skills are also valuable, but only transferable to a very limited extent.

The apprentice or employee who has been with Meister Eder for years will acquire similar skills. These are patterns that we as humans perceive and, after sufficient repetition, can recall as intuitive reactions. We can also talk about heuristics, or simple pattern reactions.

In contrast to the expert in case A, Master Eder is often unaware of the constraint between cause and effect. He has not analyzed the internal processes and converted them into if-then conditions, at least not for all the activities he performs intuitively.

Making Meister Eder’s knowledge usable for third parties, externalizing it, requires asking the “why” questions and hoping that he can and will answer them.

Unfortunately, internalized knowledge is often also a kind of protection against replaceability. For the moment of age-related retirement, this should no longer play a role. But it certainly does matter in a situation where someone is forced out of their job. “Let them see how they get along without me!”

Regardless of the motivation, however, it is also a special skill to be able to think analytically about processes that have been practiced intuitively for many years and then explain them to others. Good teachers can do this. They tend to fall into case 1.

In case 2, two people are needed to externalize: the “master craftsman” with his skills and someone who asks questions and takes notes. This second person must have sufficient knowledge to build understanding. Otherwise, it will not be possible to capture the intuition for others in a form that can be reused.

Once this externalized knowledge has been created, it is like any other knowledge content: someone with access must be able to search for and find it in a targeted manner. Once accessed, it should be accessible in a form that makes it understandable what is intended, what boundary conditions need to be taken into account, and what action should follow. The decision to do it one way or another, or not to do it at all, then lies with the new user.

Conclusions:

- Retaining knowledge within the company is an asset.

- Experts who have learned and practiced how to impart their knowledge to others have largely completed the process of externalizing knowledge.

- “Master Eder,” who intuitively does his job right but cannot explain exactly what and why, needs help.

- If this knowledge, these instructions for action, are available independently of individuals, we speak of externalized knowledge.

- Making meaningful use of this knowledge requires the next level: understanding.

Stay curious

Uwe Jarosch